A Joint Strategic Plan for Management of Great Lakes Fisheries: Facilitating cooperation for more than 30 years—and counting!

The Great Lakes fishery is one of the most important freshwater resources on earth. The fishery is worth more than $5.1 billion annually to the people of the region, supports more than 75,000 jobs, sustains native fishers, and is the essence of the basin's rich cultural heritage.

This valuable fishery is also shared and managed by two nations, eight states, the Province of Ontario, and several tribes. These jurisdictions are responsible for sustaining the resource for use today and for future generations.

Day-to-day fishery management is the responsibility of non-federal governments—the states, the province, and U.S. tribes. These governments issue fishing licenses, determine harvest levels, stock fish, and improve aquatic habitat. Federal agencies assist in rehabilitating degraded fisheries and the binational Great Lakes Fishery Commission facilitates this cooperation and protects Great Lakes fish from sea lamprey predation. All together, the work carried out by these governments is highly cooperative, complementary, strategic, and forward-looking.

This degree of cooperation has not always been the case. Until the 1950s, each jurisdiction managed in its own waters, and fishery policies were rarely consistent across boundaries. The fishery suffered from this restrictive mind-set, characterized by limited collaboration.

Today, fishery management on the Great Lakes is more cooperative than ever. To ensure cross-border collaboration, the eight states that border the Great Lakes, the Province of Ontario, three U.S. intertribal agencies, and several federal agencies are signatory to A Joint Strategic Plan for Management of Great Lakes Fisheries, a non-binding agreement through which fishery agencies commit to cooperation, consensus, strategic planning, and ecosystem-based management.

The plan allows agencies to leverage resources, avoid duplication of effort, develop shared objectives, and exchange valuable data. The result is one of the world's finest examples of transboundary cooperation. The resource, and the millions of people who use it, benefit from this unique and effective inter-governmental commitment.

The Joint Strategic Plan is rooted in 4 strategies for cooperative fisheries management: consensus, accountability, information sharing and, ecosystem management.

Consensus

All agencies must agree before management actions that affect multiple jurisdictions can be initiated. To help achieve consensus, agencies have developed shared fish community objectives for each lake. In the rare instance where consensus cannot be achieved, the plan contains provisions for conflict resolution.

Accountability

Agencies are accountable for implementing joint decisions made under the plan. The plan calls for the production of a decision record through publication of meeting minutes, agency reports, and lake committee reports.

_SMALL.jpg)

Information Sharing

The plan affirms each signatory agency's commitment to establishing consistent standards for data collection, analysis, access, and sharing.

Ecosystem Management

A guiding principle on the Great Lakes is that the resources must be managed as a whole. To facilitate this approach, the plan links fishery managers with environmental interests. For example, fishery agencies coordinate with those implementing the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement.

Lake Committees

Lake committees are the primary bodies under which the plan operates. The Great Lakes Fishery Commission first formed lake committees in 1965 to provide a place for information sharing among agencies. When the Joint Strategic Plan was signed in 1981, the lake committees became the plan's "action arms". Agencies, not the commission, appoint their representatives on the committees.

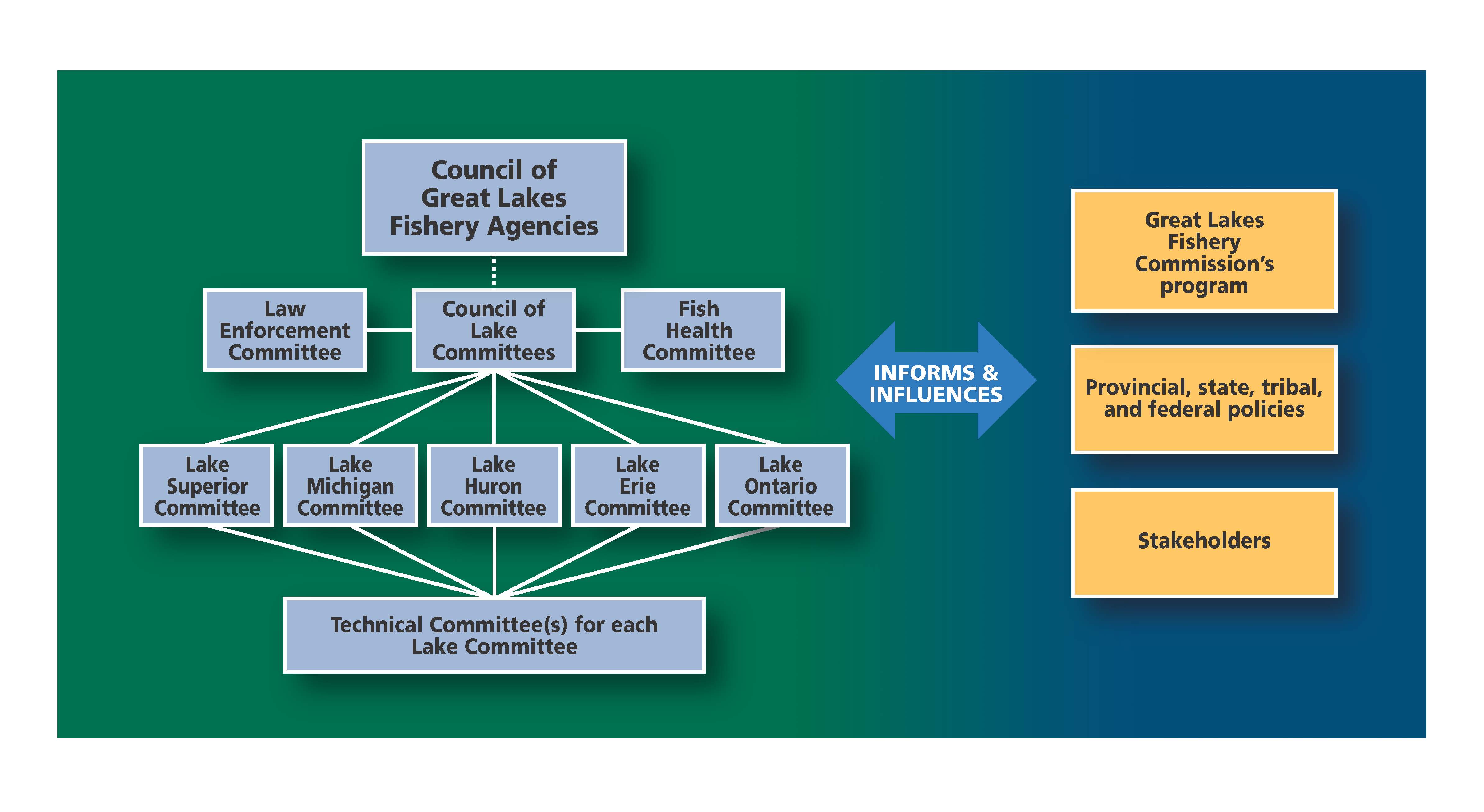

Lake committees comprise senior officials from state, provincial, and U.S. intertribal fishery agencies. Lake committee members develop shared fish community objectives, establish appropriate stocking levels and harvest targets, set law enforcement priorities, and formulate management plans. Each lake committee has at least one technical committee, a field-level body charged with collecting data, producing and interpreting science, and making recommendations to the lake committees.

To address issues of concern to the Great Lakes as a whole, all lake committee members meet as the Council of Lake Committees. Other committees, like the Great Lakes Fish Health Committee and the Law Enforcement Committee, provide specific management advice and information to the Council of Lake Committees. In addition, the Council of Great Lakes Fishery Agencies, consisting of high-level fishery management agency representatives (and non-lake committee members, such as federal agencies), ensures plans are created to address the issues of concern.

Cooperation!

Through the Joint Strategic Plan and the lake committee structure, agencies have worked together for decades to manage the Great Lakes fishery in the most cooperative, effective manner possible.

A few of the many examples of cooperative initiatives through the plan include:

- Developing shared fish community objectives and state-of-the-lake reports for each lake, as well as environmental objectives.

- Producing rehabilitation plans for key native species such as lake trout, walleye, and lake sturgeon.

- Reaching annual agreement about total allowable catch for walleye and yellow perch in Lake Erie.

- Facilitating multi-jurisdictional agreement about adjusted salmon stocking levels in Lake Michigan.

- Supporting research to advance fishery management.

- Formulating a basinwide initiative to tag and mark all stocked salmon and trout, and to analyze, share, and incorporate into management subsequent information.

- Coordinating law enforcement across boundaries.

- Supporting invasive species research, control, and advocacy for prevention.

- Signing a memorandum of understanding/agreement with the U.S. Geological Survey about the collection and dissemination of key prey fish information.

- Establishing mechanisms to detect, prevent, and manage fish disease in fish hatcheries.