USGS scientist takes aim at Great Lakes invaders

Rising Higher: A Research Lab Built from the Ground Up - Part 2

Great Lakes Researchers Go Down Under

Rising Higher: A Research Lab Built from the Ground Up - Part 1

A Monograph on Ciscoes of the Laurentian Great Lakes and Lake Nipigon

WATCH: Acoustic Telemetry Provides In-Depth Look into Fish Behavior

Eel-Ladder Style Traps: A New Lamprey Control Tool

A Lampricide Treatment: Up-Close

Lamprey Nativeness Claims Annulled by Commission's Eshenroder

A Population at the Edge: American Eel Declining at the Extremes

Celebrating 60 Years of Successful Sea Lamprey Control, Science, and Cross-Border Collaboration!

Great Lakes Scientists Use Acoustic Telemetry to Reveal the Secret Lives of Fish

Hammond Bay Biological Station: The Nexus for Research and Restoration on the Great Lakes

Big Consequences of Small Invaders

New Sea Lamprey Estimates Suggest a Dramatically Decreased Population

Conducting Research through Cooperative Partnerships: The PERM Agreement

Living on the Edge: A Closer Look at Coastal Communities

Asian Carp: The War Isn't Over

Managing the Lake Huron Fishery

Understanding Sea Lamprey: Mapping the Genome and Identifying Pheromones

- It's Getting Hot in Here!

- Big Consequences of Small Invaders

- Hammond Bay Biological Station: The Nexus for Research and Restoration on the Great Lakes

- Taking Lampreys on the Road!

- Great Lakes Scientists Use Acoustic Telemetry to Reveal the Secret Lives of Fish

Great Lakes Scientists Use Acoustic Telemetry to Reveal the Secret Lives of Fish

If you have ever gone fishing, you know that fish do not stay in one location for too long. That hot fishing spot where you caught so many fish yesterday may be vacant today. A puzzle for anglers and scientists alike is figuring out where fish move and when they will be back. Fish move throughout water bodies for a variety of reasons, such as following prey, finding mates, or seeking summering and wintering grounds. In the Great Lakes, fish have a lot of room to roam. Many Great Lakes fishes can move across huge expanses within a lake and possibly even move between Great Lakes. For biologists that study the movement of fish, that's a lot of ground to cover.

Through support from the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, the Great Lakes Fishery Commission is using innovative acoustic telemetry technology to unravel the mysteries of fish behavior. Using acoustic telemetry, scientists can track the movements of fish with remarkable precision. This detailed information allows scientists to discover previously unknown aspects of the lives of fishes in the Great Lakes, such as where certain fish spawn (a difficult job given the vastness of the Great Lakes), when fish move to and from spawning or overwintering areas, and how much mixing occurs among fish stocks. Ultimately, this information is highly valuable for improving Great Lakes fishery management.

In the past, scientists had to deduce fish movements using less precise methods such as inferring fish behavior based on capture locations. Although these methods are useful for telling scientists when a fish is present in a particular location, they do not tell scientists how the fish got there, how long the fish stayed, how many times the fish visited, and where the fish would have gone next. "When law enforcement agents are tracking criminals, they don't just wait for the criminals to commit a traffic violation or pop up in an airport - they look into criminals' phone and credit card records to get a better idea of where they have been and where they might go next," said biologist Chris Holbrook. "In a similar way, acoustic telemetry provides a record of activity that we can use to understand the habits of important fish species and to predict their next move."

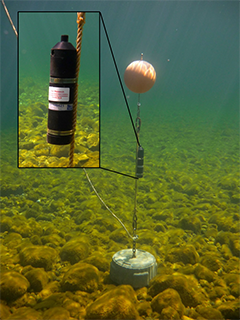

How acoustic telemetry works

Acoustic telemetry works like electronic toll collection systems such as the I-Pass or E-ZPass: an internally-tagged fish swims through a network of receivers, like a car passing through a toll-booth. The tag inside the fish - technically an acoustic telemetry transmitter - continuously "pings" a unique ID number. The receivers - small, data-logging computers also called hydrophones - listen for pings and record the date, time, and ID number for every tagged fish that swims nearby. The receivers are anchored in strategic locations: such as along migration routes, near spawning areas, and in other places of interest to scientists. In some cases, receivers are positioned in sequential lines, which allow scientists to determine fish presence/absence and movement through a constrained environment, such as a river. In other cases, receivers are positioned in an array that allows scientists to pinpoint the exact location of a fish in three dimensions, such as in an open lake. Scientists determine the location of tagged fish in receiver arrays by synchronizing information from multiple receivers (through triangulation and other methods).

The acoustic telemetry network in the Great Lakes, called the Great Lakes Acoustic Telemetry Observation System (GLATOS), consists of more than 400 receivers and thousands of tagged fish. In just three short years, scientists have already recorded more than 54 million movement records for more than ten species of fish! With each record, researchers learn more about fish movements, migration patterns, habitat use, and survival, which provide valuable insight to improve monitoring, control, restoration, and management efforts in the Great Lakes.

Acoustic telemetry discoveries in the Great Lakes

Recent advancements using acoustic telemetry in the Great Lakes include discovery of new spawning grounds for lake trout, a native Great Lakes fish that once supported a valuable fishing industry. Fine-scale acoustic telemetry tracking on a reef complex in Lake Huron revealed six specific locations - some only the size of a small bedroom - where lake trout lay their eggs. "This information is being used to determine which spawning habitats are best for incubating eggs, to identify unprotected critical habitats, and to improve artificial spawning reefs," said Dr. Tom Binder, the lead researcher on the lake trout project.

Acoustic telemetry is being used to improve our understanding of another native Great Lakes fish - the lake sturgeon which is listed as threatened or endangered in multiple areas of the region. Scientists are studying movement patterns of lake sturgeon to aid restoration in the water bodies connecting Lakes Huron and Erie. One surprising result: scientists discovered that Lake St. Clair, a hotspot of contamination and habitat degradation, serves as an overwintering area and feeding ground for these ancient fish.

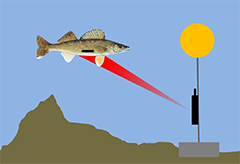

Scientists are also using acoustic telemetry to improve management of walleye, one of the Great Lakes most desirable species. Extensive tracking of walleye in Lake Huron has revealed that walleye are capable of making long migrations throughout the lake. Dr. Todd Hayden, lead researcher on the Lake Huron walleye study, explained the value of acoustic telemetry to the Great Lakes walleye fishery: "Movement information allows managers to understand how production in one area affects harvest in another. This information is being used to fine-tune and develop new management strategies that promote a healthy and productive walleye fishery in Lake Huron."

Acoustic telemetry is also being used to combat sea lamprey, one of the most notorious invasive species in the Great Lakes. The St. Marys River, which connects Lake Superior to Lake Huron, is a major contributor to sea lamprey populations in the Great Lakes. Scientists use traps in the river to measure sea lamprey abundance. To provide accurate counts, traps must be placed in appropriate locations to intercept migrating sea lampreys, but currently all traps are located at barriers, which are the "end of the line" for a migrating sea lamprey. Using acoustic telemetry, Holbrook revealed that traditional assessments underestimate the true sizes of some sea lamprey populations because many lampreys get off the train early. "Telemetry has shown us that we need to place traps in new locations and has given us the behavioral information that we need to begin designing and placing those traps," said Holbrook.

Learn more about acoustic telemetry and contribute to the projects!

If you are interested in learning more about how acoustic telemetry is being used to protect and improve Great Lakes fisheries, visit the GLATOS website: www.data.glos.us/glatos. Website visitors can explore a map of receiver locations and read more about current acoustic telemetry projects.

Anglers can also contribute to the acoustic telemetry effort by returning tags implanted in walleye and lake trout. When fishing for these species, look for fish marked with orange "spaghetti" tags on their backs (see photo, right) or fish that contain an acoustic telemetry tag inside their body cavity. If you call the phone number listed on the tags, you will be guided through a process to return the telemetry tag and receive a $100 reward for your effort! The returned telemetry tags can then be implanted into new fish, allowing Great Lakes scientists to solve even more mysteries of Great Lakes fish behavior.

Acoustic telemetry works by tracking the movement of tagged fish (top) using a network of underwater receivers (middle). Receivers log the unique IDs transmitted by tagged fish as they swim past (bottom). PHOTOS: A. Miehls, GLFC/USGS (top); T. Binder, GLFC (middle); C. Holbrook and A. Miehls (bottom), USGS

Acoustic telemetry is being used to assist restoration efforts for lake trout (top) and lake sturgeon (bottom), native Great Lakes species that once supported fishing industries but now survive in much reduced populations. PHOTOS: A. Miehls, GLFC/USGS

Invasive sea lampreys migrate upstream to spawn. Acoustic telemetry is being used to improve placement of traps used to collect lampreys during migration. PHOTO: A. Miehls, GLFC/USGS

You can get involved in Great Lakes acoustic telemetry by visiting the GLATOS website (above) and returning telemetry tags from walleye and lake trout caught while fishing (bottom). PHOTO: S. Miehls, USGS